Portraits & Musings

On the Man, Tokoto Ashanty

Every now and then, a debate erupts around Makossa’s position in Cameroonian music. At the crux of this debate is whether Makossa is, can or should be considered as Cameroon’s “official” music. Needless to say that I have almost always considered this debate more than redundant. For many reasons, but especially because Makossa, just like Cameroon, is more or less a fiction. That Cameroon is a colonial fantasy trying to cope with itself and trying to transform that fantasy into come kind of reality, like many other African countries, is surely understandable. We no longer need to stretch that. Well, that popular music genre from the coast of Cameroon. As some music scholars like Tanka Fonta have written, especially in in encyclopaedia entry on Makossa, the genre coined by Nelle Eyoum and his Los Calvinos band (named after bassist Ekwa Calvin) as a spin-off of a children’s dance, called Kossa, is actually a hybrid traditional rhythms of the Sawa people of Cameroon, as much as highlife music, palm wine music brought over by Kru and other sailors from other West African port cities, Congolese rumba, Caribbean music brought in by Caribbean soldiers who fought with the British and French armies, as well as church music brought by the colonisers especially the Protestant Christian hymns brought to Cameroon by the Germans, which were quintessentially influenced by the compositions of Johann Sebastian Bach and co. As Kofi Agawu discussed in “Tonality as a colonizing force in African music,” tonal thinking and expressions imposed on Africans in forcing them to adopt hymns like William Ralph Featherston’s “My Jesus I love thee I know thou art mine” into their repertoires, forcing the natives to adopt unfamiliar tonal regimes in the colonial era was a kind of musical violence that left psychic impacts and kept some Africans trapped in a prison house of diatonic tonality. It also goes without saying that Makossa became a potpourri of rhythmic structures from other cultural regions in Cameroon, brought in by people like André Marie Tala, Alhaji Toure, Willy N’For, or Sam Fan Thomas, just to name but very few.

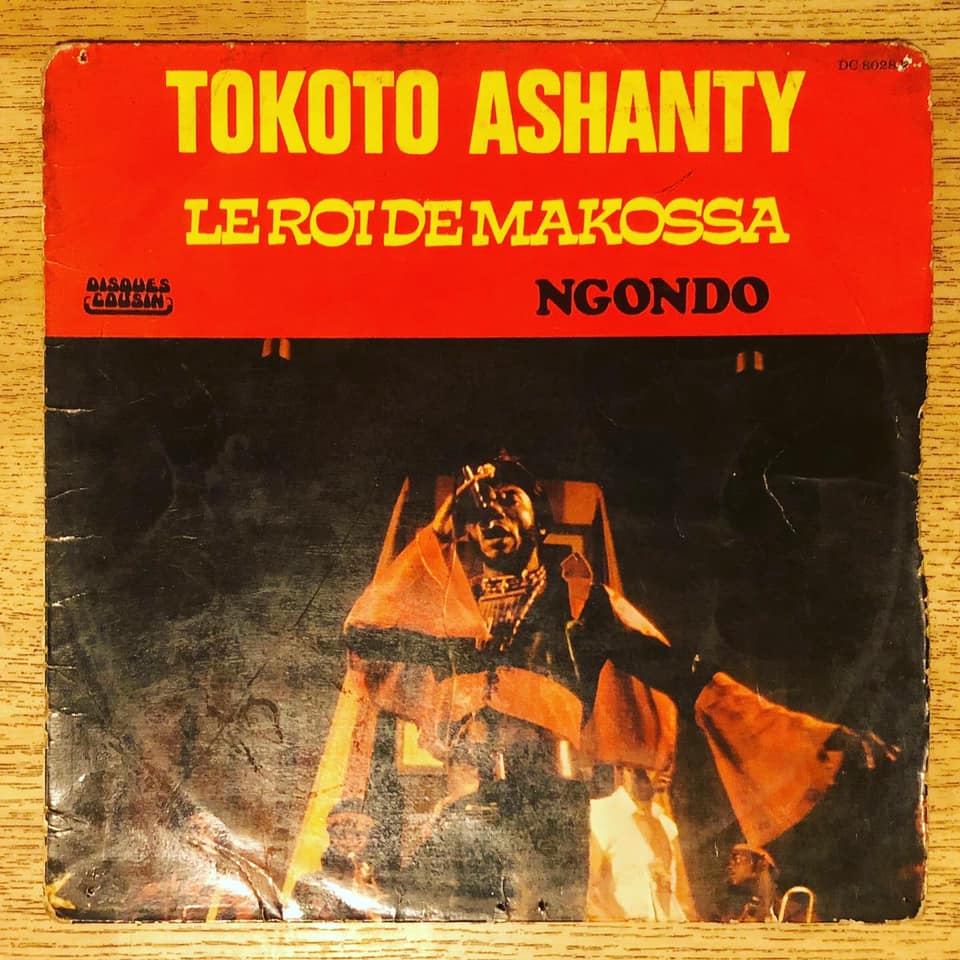

While Makossa is an interesting topic to write about, especially as too little work has been done in this domain, and especially because Makossa has been in a state of pathetic stagnation at least a decade and a half, it is unfortunately not my concern for today. My concern is rather to think about an artist that has in several ways tried to resist the colonising tropes of tonality embedded in Makossa. Indeed, ever since the creation of the genre, every generation has produced an artist that has played a Makossa that refuses the self-evidentnness of Makossa. In the generation of the late 70s and early 80s, a guy called Bunya Tokoto Emmanuel aka Tokoto Ashanty aka the amazing creature aka the creature from the black lake aka the goat man emerged with a kind of Makossa that was recognisable as Makossa, but also determinedly different in many ways. Tokoto Ashanty who is proclaimed on the sleeve of this album “Le roi de Makossa” was surely an eccentric, around and self-confident Cameroonian whose Les ASTOS consisted of a fleet of guitarists, saxophonists, percussionists, pianists and dancers.

Tokoto Ashanty, who was a multi-instrumentalist, an excellent guitarist who played amongst other with Eboa Lotin, Prince Nico Mbarga, and the legendary Nelle Eyoum at ‘Joie d’été’ in Douala, he was also a songwriter and incredible performer, didn’t just sing, he screamed as one can hear in the beginning and the course of the song “N’Gondo” with extended breathtaking “heeeeeeeyyyyyyyyys” or “heyyyyheyyyyyy” and with bouts of talking or rapping between his singing and screaming and bleating https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JAob0uzf8cw … Not only did he slightly fasten the pace of Makossa, but he also superimposed various timelines that more or less fitted to his dancing styles. He kept all the regulars of Makossa – the guitars, percussions and rhythmic horns – but accentuated with heavy congas and dundun and introduced or varied the call-and-response between his voice and the other instrumentalists, or between his voice on one pitch and another. According to Agawu, resisting tonality’s colonising tendencies happens by using and at the same time undermining it. In my opinion, a good example of such is in Ashanty’s other version “This and this” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Es6qK1XwJw where he taps deep into a repertoire of traditional motives, sonic pitches, timbres and rhythms. The synths and electric guitars are not in opposition to the congas and other percussions. Even when he sings a love song like “N’Dolo” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UxmyihB7L_g the richness is in the simplicity he can evoke with all the instruments at his disposal and with the hoarseness of his voice. The synths here in the background form the foundation to fall on, but constantly pull off the rug under your feet. This might be an epitome of the Makossa sub-genre and dance called “Wakawaka” which he was famous for. Ashanty clearly flirted with the funky beats that were coming in from African Americans like James Brown, but on the other end he was stretching the music especially within a space of narration https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dbtvija71Ik… Take note of the “Ehhhh tsha tsha tsha” and the synths again. The fireside narration as it were.

As his various aliases might have already informed, Tokoto Ashanty never just saw himself as a musician. Thats why he infused his music with lots of humorous tales and often punctuated his songs with long bouts of laughter. Besides doing music, he was active as an actor on stage and in films in Cameroon, Europe and North America. His stage presence, performances and dance styles made him a phenomenon across the African continent. When I think of Tokoto Ashanty today, I think of the video of his for “Africa danse” that was on CRTV as often as one could play a video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7yxYxU8wAE

I remember his two-part skip dancing left and right, his roaring laughter as he swung his arms like the wings of a duck left and right, and his facial expressions while articulating exaggeratedly every word he sang. At the time, the video was a sensation as it employed the technology of multiplication and the kaleidoscopic. The accompanying female dancer rolled her head to the “eiyeh eiyeh, eiyeh Africa dance,” and Ashanty almost bare-chested in his leopard quasi-traditional outfit, and barefooted enchanted the whole country. It was thus a surprise that at the peak of his career as a musician stepping confidently into the limelight, he decided to step out of the music business and became a storyteller across festivals in North America and Europe, and later dedicated some time to writing.

Maybe what has fascinated me in Ashanty’s music over the decades is the way he complicated the notions like modernity and tradition by somehow either negating them or managing the fine balancing act between modernities and traditions.

In these times when almost every young Cameroonian musician – or better said almost every young African musician – is tempted to make a sound that sounds closest to contemporary Nigerian Afrobeats from the box, it might be advisable to take a few steps back and listen to Tokoto Ashanty and Les ASTOS’ “N’Gondo,” 1978(?)

Since what we are also doing is memory work, its also important to point out this album was recorded and engineered by Njoga Mathias who was responsible for engineering several albums at the time incl Toto Guillaume Et Les Black-Styl’s “A Dikom We Mbwambo” , Mbida Mike’s “Barre Colle / Suffer”, Nkotti François Et Les Black Styl’s “Makom Na Mala / Ndol’am A Dimba Nuwe”, Meyong Ambroise’s”Ngon Mvele”, Ondoua Akono Gaston’s “Agnes” amongst others. And the master graphic designer and layout was by S. Vasco who also did a series of sleeve designs for many musicians at the time especially for the “Cameroun Partout” and “Disques Cousins” series. His signature design was string monochromes of orange or red or blue, contrasted with another primary colour on which the song titles were written and assorted image frames of musicians. Each side of the sleeves had at least 4 typefaces. S. Vasco developed a visual language that still needs to be properly appreciated and taught in schools of graphics in Cameroon today… for references check Nkotti François And The Black Styls 77’s “De Bonaberi À Douala” (green cover with a collage of Nkotti at the fore and passport size photographs of other musicians on the rare), Epee Eugene Solgary’s “Ewusu” (orange cover), Anderson Andre Bodjongo’s “Muna Kema” (green cover), Mouelle Jean Et Les Black Styls’ “Cameroun Danse” (purple cover).

About The Author

By Olaf Kosinsky – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=59796201