Brief Notes On

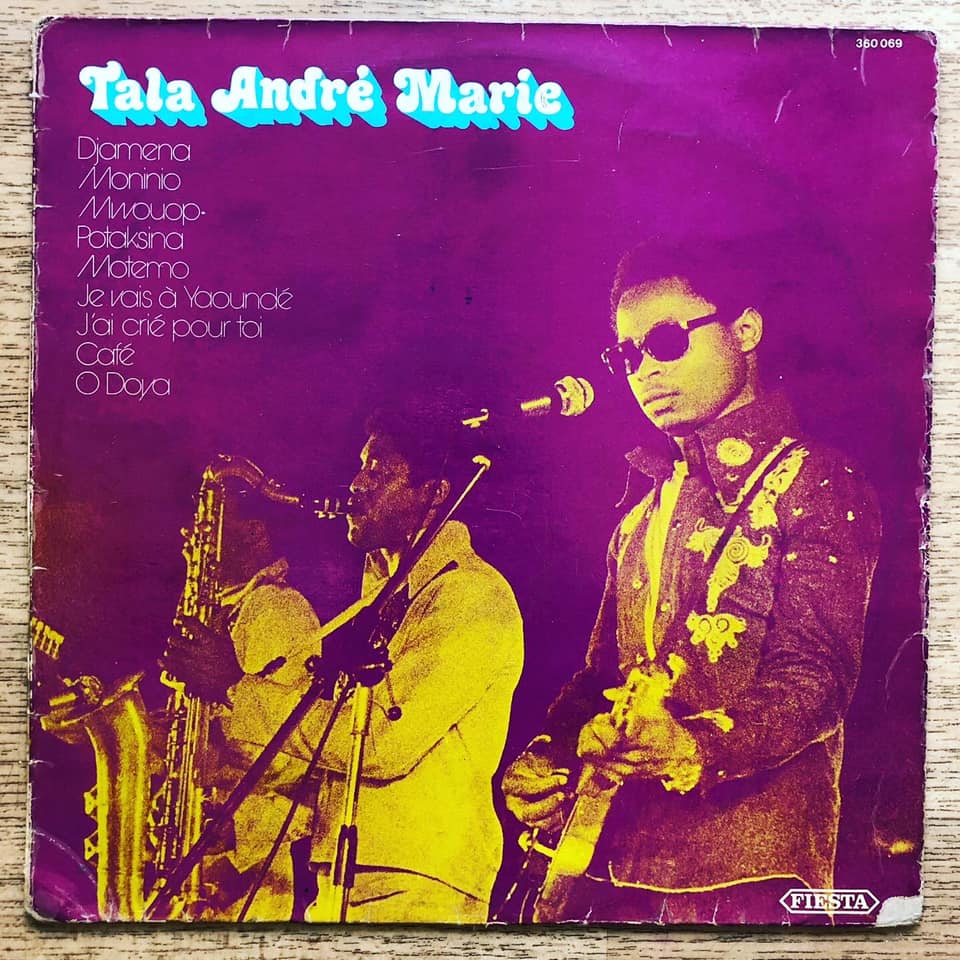

André-Marie Tala

If Elvis Presley/ is

King

Who is James Brown,

God?

Amiri Baraka “In the funk world”

The debate on cultural appropriation is one of those debates we will be stuck in forever. But it is, often, also one of those extremely draining debates without a head and a tail. Especially in the last years, not only has the debate gained much more steam and become more rampant, it has also gained in an inverse proportion and too often become shallow.

We must start by acknowledging that there is no pure culture. Culture in itself is always an amalgamation of ways of being, symbols, ideas, arts, philosophies, technologies of different peoples. Culture is never stagnant. A culture that doesn’t question itself, adapt to changing times and other shifts – space, technology, environmental conditions etc – is a dead culture. So, the adoption of elements of one culture into another is, in my opinion, not really the issue – of course the prerequisite being an even playground. Of course, the issue is the vampirisation of elements of one culture by another, especially if there is a power gradient between the two. Thus if a dominant culture takes from a dominated (politically, economically, socially, militarily or otherwise) culture, without the courtesy of even acknowledging, referencing, crediting (financially or otherwise), then this is sure cultural mis-appropriation. It is in this context that I will like to understand Amiri Baraka’s poem “In the funk world.” Now, in his lifetime, Presley was considered some kind of king of some kind of music. While whoever had the faintest capacity of seeing, let alone, listening, could perceive that most of what he did was misappropriated from African American musicians and performers like Little Richard, James Brown, Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Sonny Boy Williamson the list is too long. Still he was crowned by the white critics and establishment, king. Well, if he were king, then James Brown must be god.

Well, whoever could did appropriate something from James Brown – from Africa to Asia, from Europe to the Americas. So that really ain’t news.

The problem with the discourse of cultural appropriation, in my opinion, especially in recent times, but also in the past, has been that it too often is reduced to the colour/‘racial’ line and too often the power gradient aspect, which exists ‘interracially’ and ‘intraracially’, ‘interethnically’ and ‘intraethnically’ is ignored. In 1975, the great James Brown was invited to Cameroon, allegedly by the multimillionaire Fotso. While in Cameroon, all musicians worth the name would pay with blood to meet James Brown, who was considered a god in the Barakaian sense. An acknowledgement from someone like James Brown would have meant a world opening for many a young musician striving to break through the hard barbwires of the music business. Kind of like the Brand-Ellington complex: yes, that encounter between Dollar Brand and Duke Ellington in Switzerland in 1963 waxed by Bea Benjamin that led to the 1965 album “Duke Ellington Presents The Dollar Brand Trio.” At any rate, in 1975 in Cameroon, one of the young musicians that was chanced to meet the great James Brown was Andre Marie Tala. Then only 25 yrs old, Andre Marie Tala had already made a name as a brilliant artist for over 10 yrs with a few hits under his belt and some fame since his 1966 song “J’ai faim” and the success he had singing for president Amadou Ahidjo in Bafoussam that same year.

For the meeting with James Brown, Andre Marie Tala brought a cassette with a song he had composed circa 2 years early titled “Hot Koki”

In some circles, it was already a hit, but an endorsement by James Brown would give an international boost. James Brown took the tape, and a few months later releases a song titled “Hustle!!! (Dead On It)” interestingly, “Hustle” sounds like a phonocopy of “Hot Koki.”

Word reaches the 25 year old Tala that his work had been misappropriated by the super star. No acknowledgement, no reference, no author right fees. Nothing. So the young man takes the god to court. Long story short, it takes Tala four years in court to get his dues from James Brown for plagiarising “Hot Koki.”

But despite this wahala, Tala was as diligent and brilliant in 1975 as ever. Indeed that same year, he released the 22 (!) tracks album which was the score for Daniel Kamwa’s much acclaimed film “Pousse Pousse.” This album is a truly stunning piece of art that is very much underrated, but more on this for another time. Another album that Tala released in that same year 1975 was “Tala André Marie,” which is actually my goal for today’s post. In his 55 years of making music, Tala has been at the forefront of various music genres in Cameroon, including Tchamassi, Bend-skin, Makossa, Afro-funk, Afro-ballads and much more. This album “Tala André Marie” brings all these genres together. And it can be said that it is this wide compositional spectrum that really characterises Tala. Especially his brilliance in translating and transforming traditional music/dance formats that are normally played in royal houses or other village festivals in Bamileke land to funky danceable hits for the dance floors of Douala, Yaounde, Paris and beyond. Such is the case with the polyphonic masterpiece “Mwouop” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vpznZD2t3lc … Typically, a “Mwouop” dance of the different Bamileke groups would involve 2 or more people playing simultaneously on a balafon, accompanied by drums, whistles, njangs and sanzas mambala. The dancers – in their ndop regalia – dance in a circle around the musicians as well as rotate back and forth around each dancer’s axis. It is reserved for certain groups, especially close to the king.

But Tala, is far more than just an entertainer. He is a chronicler and socio-political commentator. One of his many songs in which this comes to the fore is “Je vais à Yaoundé.” Check out @Aude Christel Mgba’s intro of “Je vais à Yaoundé” on the @sonsbeekexhibition playlist https://www.sonsbeek20-24.org/…/playlist-curatorial…/ … Tala’s iconic piece “Je vais à Yaoundé,” which became something of an anthem of radical urbanism and rural-urban migration, was especially seminal because of the poignant questions he posed in the song: Où vas-tu paysan, avec ton boubou neuf/ Ton chapeau bariolé, tes souliers éculés/ Où vas-tu paysan, loin de ton beau village/ Où tu vivais en paix, près de tes caféiers (Where are you going peasant, with your new boubou / Your multicolored hat, your worn shoes / Where are you going peasant, far from your beautiful village / Where you lived in peace, near your coffee trees). And s/he answered: Je vais à Yaoundé, Yaoundé la capitale (I’m going to Yaoundé, Yaoundé the capital). It was at the same time an announcement and a lament. Tala was singing about a phenomenon that could be observed all over the African continent, and indeed all over the world all through the 20th century and far into the 21st century, as people moved from smaller towns and villages into metropolises and what was to become megapolises. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mUc0pTlbbd4

Another favourite on this album is “Cafe” with its synthesizers, exquisite drumming and Tala proves once more that he is a virtuoso on the guitar, a great singer and an outstanding arranger. Besides that obvious brilliance in the music, another thing that catches one’s attention is language. As it is common knowledge, Cameroon is a country in which, according to Jean-Paul Kouega’s ‘The Language Situation in Cameroon’ and other sources, some 250 languages are spoken. But at some point some unwritten law stated that to be successful in popular music, one needed to sing either in Douala, like in Makossa, or Ewondo, like in Bikutsi. Musicians from other regions of the country would go as far as adopting one of the aforementioned languages so as to have a chance of landing a hit. But then came the likes of Andre Marie Tala, Pierre Diddy Tchakounte, Tchana Pierre, Sam Fan Thomas who decidedly sang in languages of the Bamileke country – articulately and proudly. “Cafe” is one fine example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MLktg-tghm0

“Odoya” is another song engrained in traditional music from the Grasslands of Cameroon. Similar beats and rhythms can be heard from the Bamilikes to the Nguembas and beyond. This song “Odoya” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgQw91fdk9s in this 1975 album is rooted in the Mangambeu music structure of the Bangangte people, and is a kind of prelude that announces a genre that was to become popular only in the early 90s in Cameroon: Bend-skin. Bend-skin swept through the country like a tornado. A true popular music with a mix of Bamileke languages, French, English and Pidgin. The often sultry lyrics packaged in anecdotes and hints of sexuality enticed the people. Remember this is the time Cameroon is hit by one of its biggest economic crisis, in the middle of the devaluation of the FCFA, with the austerity measures labelled by the IMF that was holding the country tightly by its nuts. So imagine the people drowning their emotional depressions of the economic depression in Bend-skin.

Growing up in the Western province of Cameroon, Tala listened to lots of French chansons that took up too much space on Cameroon radio back then. It was thus impossible to not have been influenced by the likes of Johnny Hallyday, Leo Ferré, Georges Brassens or Serge Gainsbourg, who some Cameroonians grew up thinking they were local artists just because they were played so often. So one might say Tala appropriated the French Chanson culture with “J’ai crié pour toi” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-t_H3kPfj2I which he does breathe new wind into and africanises, or to put it differently, finally gives it some real life. I guess this is still a yawning gap from mis-appropriating a particular song from one of the aforementioned. And maybe the moral of the story is that even god, in the Barakaian sense, needs nourishment from somewhere – in this case André Marie Tala became the source of nourishment, parasitically, but it could also have been more collaborative and symbiotic, which, to me, is the fine line between the mis-appropriation and appropriation of cultures.