Abdulrazak Gurnah was awarded the 2021 Nobel prize for literature.

The Tanzanian novelist, who is based in the UK, was awarded the prize for his “uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents”.

Migration and cultural uprooting along with the cultural and ethnic diversity of east Africa are at the heart of Gurnah’s fiction. They have also shaped his personal life.

Born in Zanzibar in 1948, Gurnah came to Britain in the 1960s as a refugee. Being of Arab origin, he was forced to flee his birthplace during the revolution of 1964 and only returned in 1984 in time to visit his dying father. Until his retirement, he was a full-time professor of English and postcolonial literatures at the University of Kent in Canterbury.

Gurnah left Africa as a refugee in the 1960s, he was only able to return to Zanzibar in 1984. Alamy

Focus & Emphasis

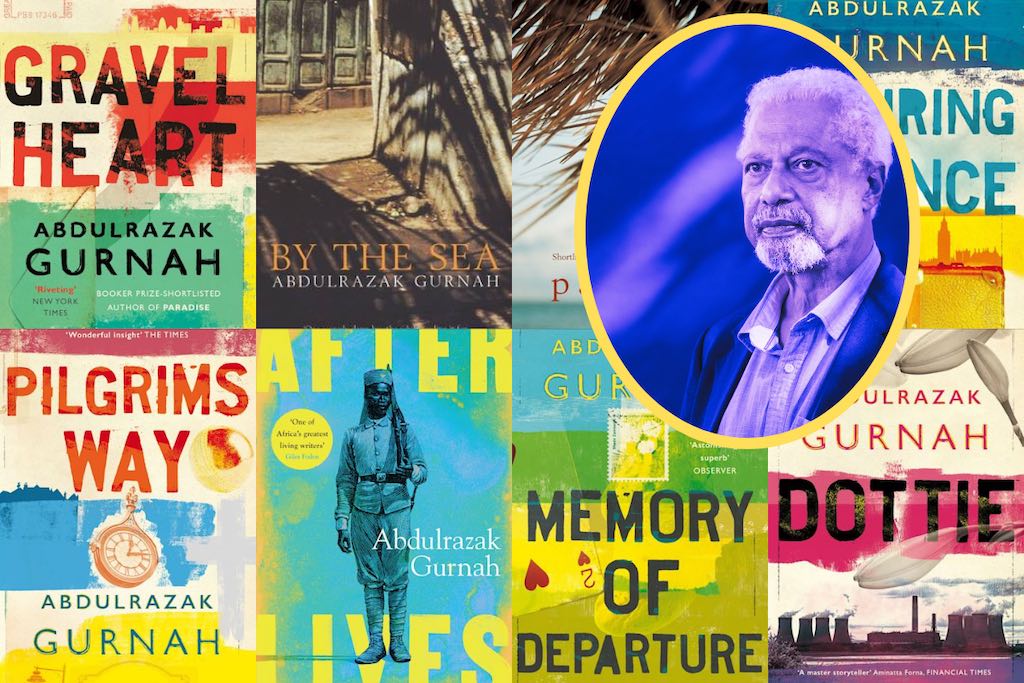

Gurnah has written ten novels to date, including the Booker-nominated Paradise in 1994 and By the Sea in 2001. His most recent novel, Afterlives, was described by the Sunday Times as “an aural archive of a lost Africa”, and indeed the opening pages of this and many of his other works take the reader directly into the realm of oral storytelling.

Afterlives is set against the backdrop of German rule in east Africa in the early 20th century. It tells the story of a young boy sold to German colonial troops. The novel was shortlisted for the 2021 Orwell prize for political fiction and longlisted for the Walter Scott prize for historical fiction.

Gurnah’s work is attentive to the tension between personal story and collective history. In particular, Afterlives asks readers to consider the afterlife of colonialism and war and its long lasting effects, not only on nations but also, and perhaps mainly so, on individuals and families.

Influence and style

His writing is heavily influenced by the cultural and ethnic diversity of his native Zanzibar. Shaped by its geographical location in the Indian Ocean off the coast of east Africa, it was at the centre of the major Indian Ocean trade routes.

The island attracted traders and colonists from what was then known as Arabia (modern-day Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Yemen and the UAE), south Asia, the African mainland, and later Europe.

Abdulrazak Gurnah, the Tanzanian novelist based in the UK. Almay

Gurnah’s writing reflects this diversity with its many voices and its range of references to literary sources. Most of all, it insists on hybridity and diversity in the face of Afrocentrism, which dominated the east African independence movements in the 20th century.

His first novel, Memory of Departure, published in 1987, is set around the time Gurnah left Zanzibar. A coming-of-age story in the form of a memoir, it follows the protagonist’s attempts to leave his birthplace and study abroad.

Consequences of Colonialism

His novel Paradise is similarly conceived as a coming-of-age narrative, though set earlier in time, at the turn of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, when Europeans were beginning to establish colonies on the East African coast. Paradise also addresses domestic slavery in Africa, with a bonded slave as the main character.

Above all, Paradise highlights the great diversity of Gurnah’s literary repertoire, bringing together references to Swahili texts, Quranic and biblical traditions, as well as the work of Joseph Conrad.

A narrow street in Zanzibar, Tanzania, where Gurnah was born. Alamy

Gurnah’s work, with its diverse textual references and its attentiveness to archives, reflects and touches on wider concerns in postcolonial literature. His novels consider the deliberate erasure of African narratives and perspectives as one major consequence of European colonialism.

In highlighting conversations between the individual and the record of history, Gurnah’s work has similarities to Salman Rushdie – another postcolonial writer who is equally attentive to the relationship between personal memory and the larger narratives of history. Indeed, alongside his novels, Gurnah is also the editor of the Cambridge Companion to Salman Rushdie, published in 2007.

Gurnah’s books ask: how do we remember a past deliberately eclipsed and erased from the colonial archive? Many postcolonial writers from diverse backgrounds have addressed this issue, from the aforementioned Rushdie to the Jamaican writer Michelle Cliff, both of whom pitch personal memory and story against a collective history authored by those in power.

Gurnah’s work continues this conversation about the long shadow of colonialism and employs a diversity of textual traditions in the process of commemorating erased narratives.

Originally Published @ The Conversation

Melanie Otto Assistant Professor in English, Trinity College Dublin